The country is not aiming for 60 percent of the populace to get COVID-19, but you’d be forgiven for thinking so based on how badly the actual plan has been explained.

THE ATLANTIC

THE ATLANTICThere was a time when it seemed possible for the world to contain COVID-19—the disease caused by the new coronavirus. That time is over. What began as an outbreak in China has become a pandemic, and as a growing number of countries struggle to control the virus, talk of “flattening the curve” is increasing. That is, a lot of people are going to get sick, and delaying infections as much as possible is imperative, so that cases occur over a long period of time and health systems aren’t suddenly inundated. Almost every country is trying to achieve this goal through the standard arsenal of public health—testing people and tracing contacts—and through more restrictive measures that include instituting quarantines, closing public spaces, banning mass gatherings, and issuing strong advice about social distancing.

But on Thursday, at a press conference, Boris Johnson seemingly revealed that the United Kingdom would adopt a different strategy. The government would no longer try to track and trace the contacts of every suspected case, and it would test only people who are admitted to hospitals. In lieu of any major social-distancing measures, Johnson instead offered a suite of soft advice—people with symptoms should stay home; no school trips abroad; people over 70 should avoid cruises.

With the peak of the pandemic still weeks away, the time hadn’t come yet for stricter measures, Johnson and his advisers said. They worried about “behavioral fatigue”—if restrictions come into force too early, people could become increasingly uncooperative and less vigilant, just as the outbreak swings into high gear. (As of yesterday, the U.K. has identified 1,391 cases, although thousands more are likely undetected.) And while suppressing the virus through draconian measures might be successful for months, when they lift, the virus will return, said Sir Patrick Vallance, the U.K.’s chief scientific adviser.

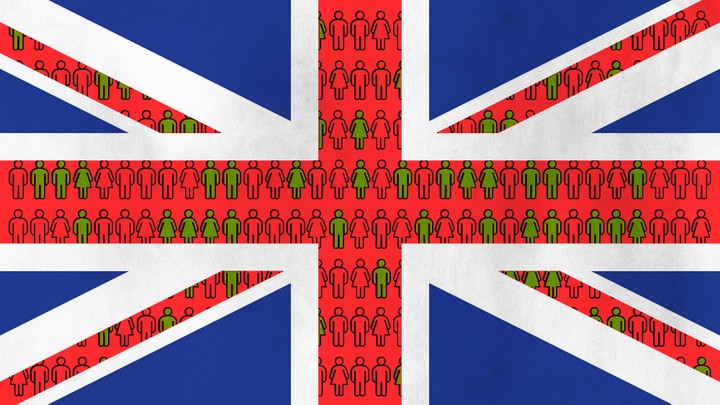

To avoid a second peak in the winter, Vallance said the U.K. would suppress the virus “but not get rid of it completely,” while focusing on protecting vulnerable groups, such as the elderly. In the meantime, other people would get sick. But since the virus causes milder illness in younger age groups, most would recover and subsequently be immune to the virus. This “herd immunity” would reduce transmission in the event of a winter resurgence. On

Sky News, Vallance said that “probably about 60 percent” of people would need to be infected to achieve herd immunity.

Almost immediately, the supposed plan came under heavy criticism, coupled with confusion that public-health and science advisers would recommend this strategy. Herd immunity is typically generated through vaccination, and while it could arise through widespread infection, “you don’t rely on the very deadly infectious agent to create an immune population,” says

Akiko Iwasaki, a virologist at the Yale School of Medicine. And that seemed like the goal. In interviews, Vallance and others certainly made it sound like the government was deliberately aiming for 60 percent of the populace to fall ill. Keep calm and carry on … and get COVID-19.

That is not the plan.

“People have misinterpreted the phrase herd immunity as meaning that we’re going to have an epidemic to get people infected,” says Graham Medley at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Medley chairs a group of scientists who model the spread of infectious diseases and advise the government on pandemic responses. He says that the actual goal is the same as that of other countries: flatten the curve by staggering the onset of infections. As a consequence, the nation may achieve herd immunity; it’s a side effect, not an aim. Indeed, yesterday, U.K. Health Secretary Matt Hancock

stated, “Herd immunity is not our goal or policy.” The government’s actual

coronavirus action plan, available online, doesn’t mention herd immunity at all. “The messaging has been really confusing, and I think that was really unfortunate,” says Petra Klepac, who is also an infectious-disease modeler at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “It’s been a case of how not to communicate during an outbreak,” says

Devi Sridhar, a public-health specialist at the University of Edinburgh.

Since Thursday, news of stricter impending measures, such as a possible

ban on mass gatherings, has been drip-fed to the media piecemeal. For example, yesterday,

ITV News reported that the government will soon tell people over 70 to isolate themselves for four months, either at home or in care facilities, “under a wartime-style mobilization effort.” But absent any details, critics were quick to point out flaws in the plan. “Who do you think works at those nursing homes? Highly trained gibbons?” asks Bill Hanage, a British infectious-disease epidemiologist based at Harvard University. “It’s the people who are in that exact age group you are expecting to be infectious.”

The delay in calling for stronger measures is also perplexing. The government has thus far recommended that people with mild symptoms isolate themselves, even though people can clearly spread the virus before symptoms appear. That’s why social distancing is so important. The government’s own

action plan even says that it will consider distancing measures “such as school closures, encouraging greater home working [and] reducing the number of large-scale gatherings.” “I think there will be a ramp-up of measures,” Klepac says. “Very soon, we’ll be asking people to reduce their contacts.”(Sure enough,

in a press conference on Monday, Johnson said that it is time for everyone to stop non-essential contact with others, and that the government will no longer be supporting mass gatherings.)

Why didn’t Johnson just roll out those measures on Thursday? Why wait, when cases are growing exponentially? Medley says the government is taking the long view. “My problem with many countries’ strategies is that they haven’t thought beyond the next month,” he says. “The U.K. is different. We’re at the beginning of a long process, and we’re working out the best way to get there with the least public-health impact.” To him, that means not rushing into panicked decisions about, say, banning soccer games or closing schools “in a way that feels good but isn’t necessarily evidence-based.”

But making a decent long-term strategy is hard when there are still two big unknowns that substantially affect how the pandemic will progress. First, we don’t know how long immunity against the new coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, lasts. When people are infected with OC43 and HKU1—two other coronaviruses that regularly circulate among humans and cause common colds—they stay immune for less than a year. By contrast, immunity against the first SARS virus (from 2003) holds for much longer. No one knows whether SARS-CoV-2 will hew to either of these extremes, and

according to one recent study, its behavior could mean anything from annual outbreaks to a decades-long quiet spell.

We don’t know how the virus will behave across the year either. Other human coronaviruses tend to peak in the winter, while lying low during the high humidity and temperatures of the summer. But it’s unclear whether SARS-CoV-2 will do the same. One study showed that, across the globe, the biggest outbreaks have occurred within a narrow band of climate. But a more granular analysis across Chinese provinces showed that the

virus can still easily spread in humid areas, and a third modeling study concluded that “SARS-CoV-2 can proliferate at any time of year.” The bottom line: There’s a very wide range of possible futures.

For that reason, critics of the U.K. strategy argue that swift, decisive action matters more than future hypotheticals do. The country’s current caseload puts it only a few weeks behind Italy, where more than 24,000 cases have so overburdened hospitals that doctors must now make awful decisions about whom to treat. South Korea, by contrast, seems to have brought COVID-19 to heel through a combination of social-distancing measures and extensive testing. Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan have been similarly successful. “That’s what you need to be doing. You go all in, or not at all. And not at all ends up like Italy,” Hanage says. “Making plans for what you are going to be doing in six months when you have a catastrophe awaiting you in three weeks is just stupid.”

Even if the virus surges back once social restrictions are lifted or winter descends, “let’s buy time,” Sridhar says. “We can use that time to get personal protective equipment in, to get beds ready, to get trainees trained properly. In the United States,

there’s a vaccine trial. There are trials of

antivirals in China. We shouldn’t give up hope.”

Much of this controversy stems from a lack of transparency: The models and data that have influenced the government’s strategy haven’t been published. And yes, these are trying and busy times, but throughout the pandemic, researchers have generally been quick to share their findings on preprint servers, allowing their peers to assess and check their work. “If your models are not ready for public scrutiny, they shouldn’t be the basis of public policy,” Sridhar says. She and her colleagues

wrote a letter calling on the government to share the evidence behind its decisions. Two other letters have also been issued, one from

the British Society for Immunology and another

from more than 400 scientists. The models will reportedly be

released within the coming days, although no firm time frame has been disclosed.

In a similar letter,

more than 500 behavioral scientists called on the government to disclose the evidence behind its contention that the public will experience “behavioral fatigue” if restrictions are put in place too early. This concept reportedly comes from the

Behavioural Insights Team, or “Nudge Unit”—a company that uses psychological science to advise the government on policy matters. But how reliable is that science? In the past decade, it has become clear that many psychology studies produce results that cannot be reproduced (the replication crisis), or that are irrelevant in all but a narrow set of circumstances (

the generalizability crisis).

In their letter, more than 500 signatories wrote:

We are not convinced that enough is known about “behavioural fatigue” or to what extent these insights apply to the current exceptional circumstances. Such evidence is necessary if we are to base a high-risk public health strategy on it. In fact, it seems likely that even those essential behaviour changes that are presently required (e.g., handwashing) will receive far greater uptake the more urgent the situation is perceived to be. “Carrying on as normal” for as long as possible undercuts that urgency.

Without strong guidance, British institutions and citizens have begun making their own decisions, going well over what the government recommends. Universities haven’t been told to close, but

many have, sending students home, moving classes and exams online, and postponing graduations. Many care homes will not be admitting visitors. Soccer leagues have been suspended. The Queen has canceled public engagements. The Scottish government is planning to close schools and

expand testing.

“When you cannot rely on your government, there are still things that you can do,” Hanage says. “You are able to limit your contacts, which will not only protect you but also your community. If you don’t start to isolate yourself as much as you can, they’re more likely to die.”

“We really need people to engage and to sustain individual control measures, like social distancing, for months at a time,” Klepac adds. “We’re in this for the long term and we need everyone to do their part. It is a very big ask.

Share...